Real Smart Cities are not user-friendly

The European debate on Smart Cities should focus less on “user-friendliness” and more on open access and engaging citizens in the complex political issues involved in the creation of technologies and cities.

A few weeks ago I attended a meeting in Pakhuis de Zwijger in Amsterdam about the “Smart City.” The concept of the Smart City points to a future ideal in which digital technologies, implemented in domains such as health care, transportation, education, finance, and politics, will make urban life more efficient, sustainable, inclusive, and hence “smart.”

A technology expected to make cities “smart” was recently introduced by the Waag Society in an article in the Amsterdam newspaper Het Parool: Amsterdammers can apply for a so-called Smart Citizen kit, a small computer with sensors that measures toxic substances in the air and streams these measurements onto a website where they appear on a map. The article was entitled “To Measure Means to Know” (Meten is Weten), suggesting that the kit is a kind of scientific tool that gives citizens power to really understand their environment.

Distinguishing between people and technology

In Horizon 2020, which outlines plans for the European future, several billion euros have been made available to support “multi-stakeholder” networks that offer good ideas for realizing this Smart City future. Hence, it is very lucrative for institutions and individuals in cities across Europe to claim a frontrunner position in realizing the Smart City.

At Pakhuis de Zwijger, one of the speakers did announce herself as part of a frontrunners group. An important part of her vision of the future of the Smart City is that it should not be about technology, but about people and the question how technologies can be applied to actual social problems. This distinction between technology on the one hand and the world of people and applications on the other is a recurring theme in the many other Smart City discussions, debates, and conversations I participated in.

This distinction sounds sympathetic, appealing to the user-friendliness of technology. Yet, to me, as an anthropologist who studies technology as a cultural practice, this distinction has always seemed odd. It suggests, somehow, that technology comes from outer space in neutral form and only after it has landed on earth achieves political, cultural, social, and psychological meaning. The call for user-friendliness often implies a call for making invisible how the process of technology creation is deeply imbued with cultural and political meaning.

Different types of ideal futures: The creation of the Air Quality Egg

In the past two years I have seen this from close by. I followed the creation of a predecessor of the Smart Citizen Kit, the so-called Air Quality Egg (hereafter “AQE” ): The AQE was made by an international network of entrepreneurs, programmers, engineers, activists, “community organizers”, and anthropologists like myself. We met regularly and stayed in touch through a wiki, mailing list, and website. During this process many decisions had to be made about the hardware, software, and the potential uses of the AQE.

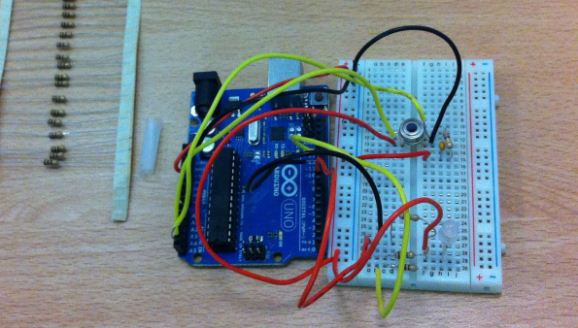

Visible chips and wires on a sensor board

In this process, two problems in particular came up regularly. The project appealed to the ideal of transparency and of making that otherwise elusive object, “air”, scientifically measurable and shareable. Yet, the sensors that were used were cheap and not at all reliable in a scientific sense. Another problem was the fact that the hardware was produced in an Open Source way, meaning that no-one could claim exclusive ownership. Yet, the platform that collected the data produced by the AQE was owned by a commercial company. Throughout the process, this platform became increasingly commercialized. It now offers long-term data storage and full flexibility in the way that data can be made accessible, only to paying customers.

Engaging with these issues while following the making of the AQE showed me how ostensibly technical decisions were also always decisions about power. Depending upon the positions taken by the AQE creators with respect to these issues, the object meant different things, pointing to different types of futures, and, by extension, to different ways in which the ideal of this alleged “Smart City" can be realized.

During the process we were always told that in the end the AQE should be relevant not only to us “early adaptors” and geeks, but also to average users, who can apply it to their real-world problems. Yet, when the messy prototype that we worked on changed into a “user-friendly” object enclosed in a shiny casing, the very real-world issues we had been wrestling with were also closed off.

Air Quality Egg as the final product

From an object that evoked many important discussions about society’s belief in science, the meaning of data, and the role of capitalism in technology development, the AQE now became a user-friendly product that could either be switched on or off. And the platform that streamed the data produced by the AQE stopped facilitating discussions about the actual meaning and reliability of the data, and instead adopted marketing language, selling “transparency”, “efficiency”, and above all, a Plus account with helpdesk facility.

Ultimate user-friendliness: Open processes and discussions

If the concept of the Smart City is to be more than a story that turns citizens into consumers of ever-new technologies, I think we should be more precise about what we mean with “user-friendliness.” If it means that we close off our information technologies behind flashy interfaces and in shiny casings, while outsourcing the difficult questions about power and value to specialized helpdesks and separate spheres of technology development, Smart Cities should not be user-friendly.

Just as we should perhaps stop distinguishing between frontrunners and followers when it comes to envisioning future cities, we should stop differentiating between the world of geeks and users, and between “technology” and “people.” Instead, anyone should always be invited to have a look “in the kitchen” of technology, and to take part in the discussions of power and value that go into its production. If anything should be made “user-friendly” it is access to those discussions and processes.

In the following months I will study in how far this Smart Citizen Kit facilitates these discussions. I will keep you posted!

0 Comments

Add a comment