Zine-making in Leiden: workshops on experimental print publications

Can academia still be fun and experimental? Maybe it can with the printing, folding, and collage techniques of zines. In two hands-on workshops, Sander Hölsgens and James McGrail aimed to find out. In this blog they discuss what they learned, and how zines can become a useful part of an anthropologist’s toolkit.

Can zine-making be an academic practice? And, if so, what will we gain from such an experimental format? In the spring and fall of 2023, we organised two hands-on workshops to explore zines as a teaching tool and modality for research output. We found that zine-making holds the potential for instilling creativity, care, and solidarity in academia. In this blog, we highlight our main take-aways from the second workshop – held on 26 September 2023 and tailored to students and staff of the Leiden Institute of Cultural Anthropology and Development Sociology. Some sections of this blog are derived from the print publication we made during the workshop.

You can download the pdf of the co-produced zine here, or reach out for a print copy.

What's all the fuss about?

Zines are non-commercial publications, often engaged or political in form and content. Using experimental printing, folding, and collage techniques, zines afford creative and critical modes of output. Akin to what Phiona Stanley calls ‘low-tech blogging’, zines tend to be made-in-the-moment, include auto-ethnographic or autobiographical nudges, and are ‘lavishly illustrated’. Zines exist somewhere between fact and fiction, criticism and art, activism and diary-style writing. They truly are sui generis – unique and incomparable.

Both of us have made zines for a number of years. Not unlike field notes, making zines is a mode of making sense of the stuff we do, observe, and experience. But whereas field notes are usually translated into neatly organised research findings (despite notable exceptions such as Michael Taussig's ‘I swear I saw this’), zines are usually structured around unfinished thoughts, unpolished images, and crude design practices. In short, zine-making opens up a space for considering work-in-progress as a potentially vigorous and rigorous way for doing reflexive research.

Parallel to being a research method, educators across the globe are turning to zines and zine-making as teaching tools. What if, instead of one-directional lectures, we ask our students to co-create a zine on the topic at hand? Such an approach would foreground the knowledge and experience present in a specific room, allowing for a situated pedagogy: co-producing a zine means attending to a diversity of knowledge and modes of expression punctuating the classroom. Because of its pamphlet-style sensibilities, it fosters horizontal learning strategies.

But how do we begin?

Whether drawn or written or collaged or stuffed with hyperlinks, zines offer an accessible medium because of its low-key and low-tech approaches. A single sheet of paper and some drawings tools are more than sufficient to make your own 8-page zine. Completing such a zine, we found, takes anywhere from thirty minutes to three hours – perfect for an afternoon workshop.

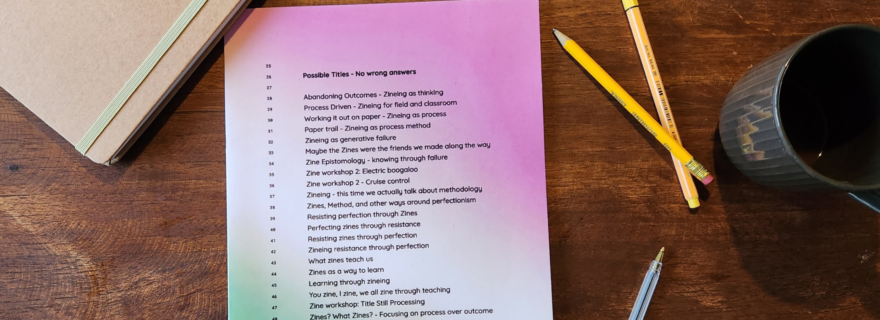

During our workshop in the fall of 2023, we asked: what if we consider zines and zine-making as a starting-point, an orientation, a standpoint? How can zine-making help us imagine, articulate, and hack how we actually begin (with research, learning, teaching)? What's our point of departure? And how do we proceed from there? These questions are particularly inspired by Sara Ahmed’s Orientations: Toward a queer phenomenology (2006). During the first half of the session we introduced zine-making as a reflexive and speculative praxis; in the second half we invited all present to make a zine tailored to a project they're about to begin. While no preparation was necessary, we invited attendees to bring materials (written, visual, tangible) relating to a new project that they were willing to cut up, assemble, and edit into a collage.

The broader aim of the workshop was to advocate and perform zine-making as an addition to the ethnographer's toolkit. We speculate how zine-making may enable us to break away from the static syllabus to modes of learning that resonate with the caring and patchwork sensibilities of ethnography. Building upon the premise of radical zine-ing to empower and inform practitioners and collectives, making experimental print publications together challenges scholastic celebrations of perfectionism and achievement. Our hope: fostering a learning space that’s a tad more attentive, engaged, and enworlded.

What did we learn?

Across the two sessions, students and staff produced over thirty zines, twenty six of which are included in our two print publications. These zines covered topics as varied as gardening, wakeboarding, and Palestinian solidarity in Indonesia. What consistently emerged was the theme of messy processes, incomplete ideas, and failure. Interestingly, these zines do not lament these struggles, but instead embrace them. As one zine puts it: “make a mess... then clean it up”.

One of the perks of zines which we promote in these sessions is their immediacy and crudeness. But how long does this take to realise? During our first workshop we left only half an hour for zine-making. As a result, a few workshop participants felt rushed, and some were unable to complete their work. To account for this, our second session was longer and we – as organisers – talked less. We dedicated an hour and a half for people to create. Paradoxically, the availability of more time seemed to reintroduce hesitation and perfectionism. Having too much time might take away some of the freedom and spontaneity zines aim to engender.

Starting from scratch can be difficult. This is why we used prompts as a point of reference for all attendees. Narrowing down the scope of a project can increase the creativity of an output. Reviewing the submitted zines, we see how the prompts informed the authors. During the first session, we asked people to look at a problem they were struggling to explain in their research. For the second, we focused on prompts related to process and making. While diverse in terms of topical focal points, the reverberations between the submitted zines is remarkable.

Zine-making at CADS

In the COMPACCT zine “Print Politics”, Anne Pasek writes how “we are all very indebted to the tools that we use to think.” We believe that zines are a meaningful addition to the ethnographer’s toolkit. It won’t replace the praxis of writing papers or making ethnographic films. But making zines can elicit something increasingly rare in academic pursuits: the fun and the quirky experience of experimentation.

The zine-making workshops are organised as part of the newly formed The Field and The Classroom research cluster. Reach out to Sander [s.r.j.j.holsgens [at] fsw.leidenuniv.nl] if you’d like to join or find out more.

1 Comment

Using experimental printing, folding, and collage techniques, zines afford creative and critical modes? Visit us <a href="https://ensiklopedia.telkomuniversity.ac.id/cara-mudah-merangkum-video-youtube-menjadi-teks-secara-otomatis/">Telkom University</a>

Add a comment