On the Corona crisis and numbers

Dutch policy has placed health metrics at the center of discussions around the Corona Crisis. Numbers visualize the urgency of the societal threat and form the basis for policy intervention, but they are also feared, celebrated and presented as proof that ‘we are all in this together’.

A figure of speech

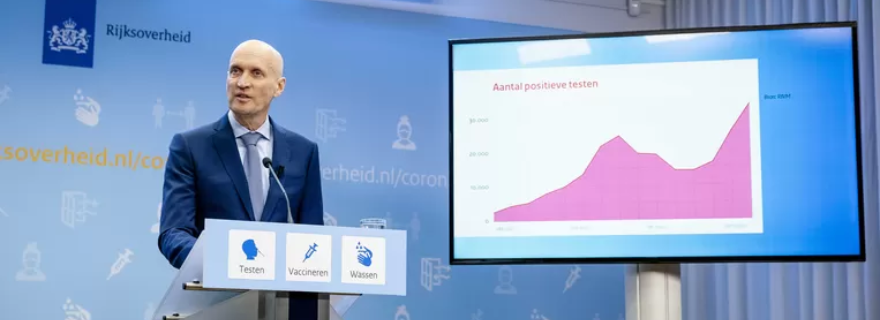

"Good evening. 16.364 new infections. Sixteen thousand – Three hundred – sixty-four. That was the number of yesterday."

– Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte (12-11-2021)

If, like me, you have tuned in to the corona press conferences in the Netherlands over the years (has it really been years?), you cannot have missed that numbers featured prominently in the government’s address to the nation. Rutte and his ministers spoke of infection rates, of ‘flattening the curve’ or invoked the infamous R-figure to convey the extent of the crisis unfolding in our midst. For me personally, as the passage of time became increasingly meaningless, the press conferences provided a regular interruption to the monotony. And, like the weekly regularity of the press conferences, ‘let me start with the numbers’ became a reassuring phrase. It signaled that policy decisions were based on careful research and verifiable facts. That beyond the silent streets, the many deaths and near complete suspension of social life, amidst the radical uncertainty, there was some semblance of control over the crisis.

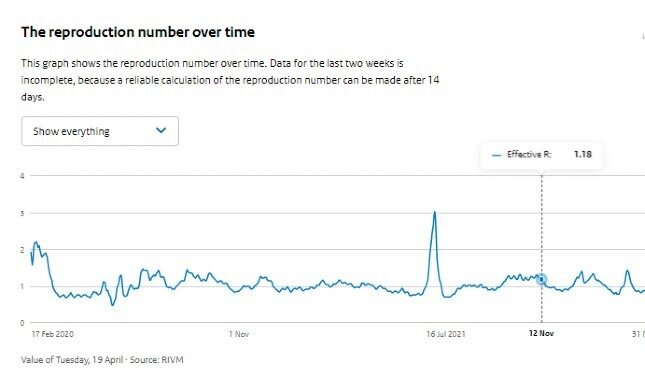

Apart from the curiously soothing effect which the repetition of corona numbers had on me, they also piqued my interest. As someone who studies the relationship between crisis and quantification, I began to pay attention to the ways in which numbers shaped the narrative. Numbers and collective counting are important ways in which we think about and order the world around us. For many, statistical trends gave the Corona Crisis tangibility as a collective societal issue. Apart from their frequent presence in the press conferences, think also of the Dutch Corona Dashboard. Here the public is updated daily on a wide variety of health metrics; from positive tests in the last 7 days and number of deaths to virus particles in wastewater and public compliance with Corona regulation. As a tool of collective counting, the Dashboard visualizes the crisis in powerful numerical terms through graphs, maps and percentages. It displays, with seeming cold rationality, the scale and seriousness of crisis that would otherwise, to many of us, remain hidden.

The more immediate goal of the dashboard, meanwhile, is to keep track of indicators which inform policy decisions. The idea is that when indicators reach a certain value it sets off an ‘alarm bell’, which would trigger new measures. With this rationale Dutch politicians routinely make themselves subservient to the numbers. After all, few would contest that an increasing R- number casts an ominous doubt on the future and that it warrants a strong societal response.

We are counting on you

Apart from being tools of governance, these graphs, maps and percentages are also powerful symbols signaling our collective experience with living through the corona crisis. For a long time, a sharply rising line on a graph visualizing infection implied an impending societal threat. It led to fear, attribution of blame and sometimes disbelief. It invited discussion at the dinner table and strong political interventions. Meanwhile, declining lines in the same graphs are celebrated as a success of policy and a confirmation of discipline and morality within society. This narrative, where the numbers showed that ‘we are all in this together’ came up frequently in the press conferences. For instance in November 2020, as the Netherlands was enduring its first (partial) lockdown, Rutte appealed to ‘our’ collective morality by stating:

‘The numbers show that the measures are working. Or actually that our behavior is working. And also that famous R, the reproduction number is now clearly below 1. […] I think that this is a compliment to us all’ – Prime Minister Mark Rutte (17-11-2020)

Such statements clearly signify that ‘we’ are collectively responsible for the crisis and that the moral conduct of society can be measured through abstract statistical indicators. Being the anthropologist that I am, my ears instinctively prick up when politicians make references to ‘us’. It begs the question: who does this ‘we’ refer to? Who is it actually that Rutte is complementing? I have to conclude that substantive answers to such questions are complicated (another anthropological tendency of mine). However what can be said is that in the last two years public health metrics became unavoidable to answering these kinds of questions. Looking beyond the rationalist façade of numbers allows anthropologists to catch a glimpse of how people give meaning to crisis as a social phenomenon and imagine a collective moral attitude to it.

0 Comments

Add a comment