Co-labouring for Sustainability: the value of transdisciplinary collaboration between mining actors, artists and researchers

Co-labouring in research projects generates new perspectives and creates shared experiences and moments of enjoyment. Reporting on a recent workshop in Ghana, Robert Pijpers and Sabine Luning show how co-labouring both bridges and reveals inequalities inherent in research practices.

This blog originally appeared on the Gold Matters website on 4 May 2020.

With special thanks to all participants of the workshop

Between 12 and 15 January 2020 the Gold Matters project (a transdisciplinary research project which studies whether and how a transformative approach towards sustainability can arise in Artisanal and Small-scale Gold Mining) organized its first ‘Sustainability Conversations Workshop’ in Kejetia, Northern Ghana. The workshop focused on transdisciplinary collaborations around visualisations of gold mining spaces, gold miners’ lifeways and projections of sustainable futures. It involved residents of the Kejetia mining community in Northern Ghana (including male gold miners, women involved in processing ore and schoolchildren), Gold Matters researchers from Europe and West Africa, a cartographer, West African artists and gold miners from another research site in the south of Ghana who had travelled with the research team to the north.

Kejetia - Ghana

While being a relatively small mining community in the north of Ghana, Kejetia has a significant and long gold mining history, influenced by mining mobilities. In the 1980s and 1990s many artisanal miners from southern parts of the country travelled to the north, and even though most of them left again when prospects in the South improved once more, several of the connections were sustained. Recently, Chinese miners have started to work in Kejetia, as they have elsewhere in the country. With both positive and negative effects, often coexisting in single situations, this development has significantly shaped Ghana’s (artisanal and small-scale) mining sector as research by, for example, Hilson, Crawford & Botchwey and Luning & Pijpers shows.

Sabine Luning (one of the PI´s in the Gold Matters project) and her students from Leiden University have established a long-term collaboration with miners in Kejetia (see for example van de Camp). In addition, project member and artist Nii Obodai has undertaken photography projects with miners and others in the area. This facilitated the possibility of organizing this workshop and being warmly welcomed by the community. Moreover, some of the participating miners from Southern Ghana were among those miners who explored this area in the 1980s and 1990s, which offered a profoundly interesting temporal perspective to our transdisciplinary work and the way that as outsiders we were able to read and interpret the landscape.

Visualizing mining space

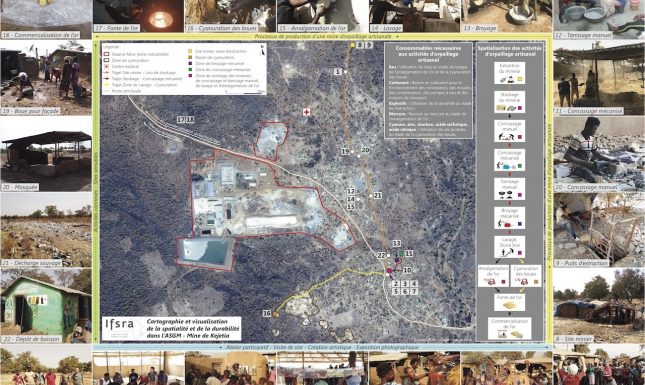

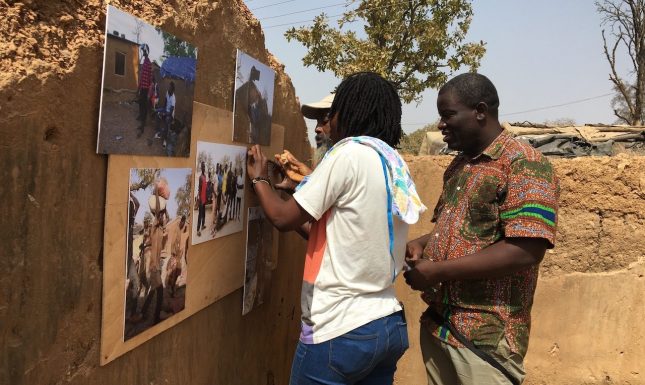

As indicated, our workshop is part of a series of ‘Sustainability Conversations’, which consists of events focused on transdisciplinary interaction and collaboration around sustainability challenges in the artisanal and small-scale gold mining sector. In order to facilitate conversations over sustainability issues, several activities were carried out. These included the mapping of Kejetia’s mining space via ‘walk-alongs’ using mobile mapping devices; the setting up of a photographic pop-up exhibition; and a photography workshop with schoolchildren. In all these activities, a recurring form of collaboration focused on visualisations, whether this concerned locating specific places and tagging photos onto a map, the portraying of local and global artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) practices in the exhibition, or schoolchildren photographing their everyday lives in the gold mining community.

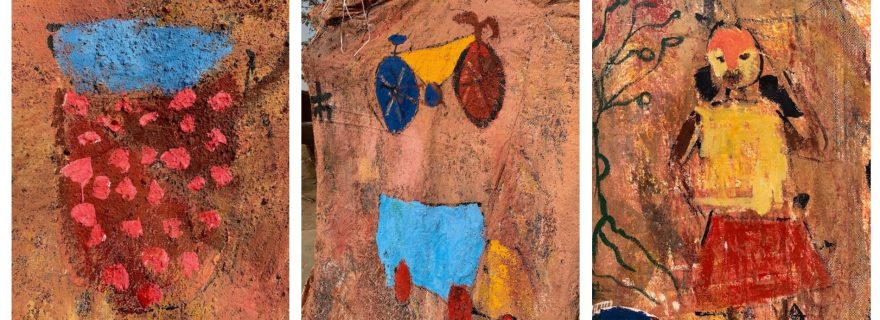

In addition to the above, an important aspect of co-labouring during the workshop was initiated by our team member Christophe Sawadogo, an internationally renowned painter from Burkina Faso. Together with women of Kejetia, Christophe created an installation artwork, using bags that had served for carrying mining ore, together with paint which had been deliberately mixed with local earth. The wood construction around which the bags were tied symbolized a shaft. The act of colourful painting of the bags resembled the way in which women paint their houses. As a totality, the artwork became a site for co-memorating the gold miners who had died in two tragic underground mining accidents recently (see here and here).

Discussing best and other practices

During all our activities discussions about the sociality of the landscape as well as about specific mining practices and their effects on sustainability challenges were most prominent. During the setting-up and formal opening of the exhibition, for example, various mining actors asked questions and started to discuss with each other what the pictures were portraying, both when watching familiar practices as well as portraits of unknown mining techniques, for example from Brazil. Similarly, during the ‘mapping walk-alongs’ the team engaged in conversations, both with one another and with those working and living in the places that were mapped. Walking with researchers, artists and miners ensured that attention was drawn to different landscape features, whether these involved machines, abandoned sites, drawings on walls or public bathing facilities, thereby generating a diverse reading of this mining landscape.

During the ‘walk-alongs’, miners from the North and the South engaged in in-depth discussions about underground structures and how to target the gold, while at other places miners advised those who were exposed to high amounts of dust while processing material. For example, a debate emerged over whether it wouldn´t be better to wear, mouth, nose and eye protection? Likewise, when discussing with a group of women who were sifting sandy material, they asked the women how they assess their health risks and how prevention could safe lives and costs. Miners from the South conveyed how, in the South of Ghana, up-scaling in technologies had made some of the health threatening steps in ore-processing obsolete, others argued how such up-scaling would marginalize women. This raises a key question: what information and options are available with regard to lives and livelihoods? What are mining actor’s concerns and priorities? And how does that influences perceptions about and solutions for sustainability issues?

The value of co-labouring for sustainability

Co-labouring adds tremendous value to the work research projects such as ours are doing; work which aims to generate (academic) knowledge concerning challenges and opportunities for (sustainability) transformations. For example, co-labouring foregrounds multiple perspectives, since different people look with different eyes based on different expertise, sensitivities and interests. This means that we can understand the mining landscapes in which sustainability challenges emerge in more diverse and holistic ways. At the same time, the team members responsible for organizing the workshop had moments of discomfort: visiting team members were ‘in the lead’ in several of the events, and perhaps they were learning most (de la Cadena). This awkwardness brought home that co-labouring does not only bridge inequalities, it can also make them more visible than mainstream research projects would do. This strengthens our joint commitment to address how events of co-labouring can be sustained in long-term relations with joint agendas and tangible benefits for mining communities.

Throughout the workshop, most valuable interactions occurred between collaborating miners, posing questions to each other, while simultaneously explaining to researchers why these questions are relevant. In our workshop, this was illustrated by the role played by one of the participating miners who, as a person from southern Ghana, had travelled to this area in the 1980s to be involved in mining and the introduction of new techniques into the 1990s. He had known Kejetia from long before the Chinese miners arrived. Through our ‘walk-along’ and mapping work, this miner opened our eyes to aspects of mining that were partly visible on the ground, but also had invisible dimensions, insofar as being underground. He took us to what he considered to be the best site, where he had mined in the past, intriguingly named the ‘World Bank’. In the present the underground of the World Bank is the scene of stiff competition between small-scale miners and a Chinese mining company. The miner was showing us to look at ‘situational transformations’: social dynamics in specific spaces, marked by on the ground and underground features, but also by histories of cross- regional mobility, of which local toponyms turned out to be telling the tales of such longer histories.

A focus on visuals and visualizations has proven an important ingredient in our work. Not only did we co-labour in mapping as well as drawing and filming to make underground wealth and work visible, co-labouring with picturing and painting were just as valuable for sustainability conversations. Mining actors, artists and researchers alike were all eager to make, see and share pictures. The participatory artwork by Christophe Sawadogo generated similar enthusiastic responses as participants enjoyed the process of coming together for the purpose of making art and bystanders were drawn to this activity and into discussions. Actually, the collaboration around the art installation added substantially to the ambiance of amity and alliance.

The workshop showed how co-labouring, engaging in projects together, contributes to building relationships of trust, and transforming research relations into friendships. It does not eliminate inequalities inherent in research practices – on the contrary, it may even highlight them better - but common learning, exchange of experiences and expertise, and enjoyment serve to build bridges in interactions between the participants, which make the events most valuable in themselves and a source for envisioning vistas for sustained co-labouring for the future.

These observations are key to more nuanced discussions about sustainability and ASGM. Everywhere in the world, artisanal and small-scale miners not only face economic hardship, they are also confronted with legal and social criminalization, often legitimized with one-dimensional causal reasoning about the impact of their activities on the environment. As such, engaging in discussions from multiple angles, collaborating around joint tasks and maintaining good relations are key in developing fair understandings about artisanal and small-scale mining and its dimensions of sustainability, including social, economic and environmental impacts and possible solutions.

0 Comments

Add a comment