Armenians from Turkey: From silence in Istanbul to cultural production in Beirut

For Armenians in Turkey the twentieth century was marked by silence. This strongly contrasts with the history of those who left the country. In Beirut, the elderly speak emotionally about their experiences; younger people grow up with revolutionary songs.

Istanbul: New research

A new research topic often comes to you when you least expect it, and it can take years before you are able to take it up. In the first week of my PhD research on Kurdish singer-poets (dengbêj) I met and interviewed the very first dengbêj in Istanbul. Dengbêj Cîhan had lived his life in a Kurdish village and with a Kurdish family, but he told me that his father was an Armenian from the Sassoun region, who had survived the genocide. The more he told me about his father’s story and how he related to it, the more I felt fascinated by the topic.

I like these simmering research ideas, waiting to be worked on when the time comes. Somewhere somehow you get the chance, and you take it. For me that time came after I had finished my dissertation and received a small post-doc funding.

Sassoun: Silent history

The Sassoun region is situated in eastern Turkey, not far from the large city Diyarbakir, which is now often referred to as the capital of Kurdistan. However, before the 1915 genocide the region had a strong Armenian presence. Until the late nineteenth century Sassoun had remained virtually independent from the Ottoman state. It had its own local rule, and a strong culture of music and dance. The ‘David of Sassoun’ story is today regarded as Armenia’s national epic. In Turkey there are only fragments left from this Armenian history, plus a century of deafening silence that was broken only very recently.

Beirut: Vivid reminiscences

Coming from a place where silence is so dominant, I found it a stunning experience to visit Beirut with its visible and active Armenian community. Everywhere you see Armenian names and signboards written in the Armenian alphabet. There are Armenian shops and offices in the neighborhood Bourj Hammoud, where Armenian is the most common language. The commemoration of the genocide is a yearly event with thousands of people walking towards the central square. There are community organizations for each region where people come from.

Armenian bakery Marash, called after the town of origin in Turkey, in the Bourj Hammoud neighborhood, Beirut.

As a consequence of their Armenian education, the close ties within the community, and the many cultural activities offered, young Armenians in Beirut today often feel very connected to the history of their grandparents. They demand a recognition of the genocide and seek justice by claiming back the lands that once belonged to their grandparents, and which they often continued to long for until they died.

An elderly man shows pictures of the Sassoun rebels

Sona: Songs of sorrow

One of the people I spoke with is Sona, a woman who was born in 1933 in a village not far from Qamishli in Syria. She learned Armenian from her father and in the Armenian school where she went to, and Kurdish from her mother. Both of her parents came from relatively well-to-do families in Sassoun who had been protected by neighbors, and survived the genocide. Sona’s family nevertheless moved out of Turkey in the early 1930s, when they saw that the situation did not improve sufficiently. From Turkey they moved to Syria, and later from Syria to Lebanon.

Together with Sona

When Sona was nineteen years old she married an Armenian man from a town close to the Iraqi border, and went to live there. His family had also remained in Turkey until the 1930s. They did not speak any Armenian, and for years Kurdish became the language Sona used most. For weddings and celebrations, church meetings and funerals, these Armenian families sang all their songs in Kurdish.

Once in a while people would gather in one of the houses, and they would sing laments about the genocide; Sona remembers these meetings well. These were moments of sharing the intense sorrow about all the people that had vanished. Song followed song about what had happened, who had been killed, and who had gone missing. During these sessions of mourning, people sang and cried together.

April 24th commemoration of the Armenian genocide, Beirut

Arin: Songs of revolution

Sona’s daughter Arin was born after her parents moved from Syria to Beirut. She went to an Armenian school and told me that she was a zealous Armenian in her childhood. She grew up with revolutionary songs. Many of these songs speak of the Sassoun heroes who revolted against the Ottoman regime. They became immensely popular, widely known nationalist Armenian songs. This militaristic march music contrasts strongly with the sad lamentations that her mother once sang.

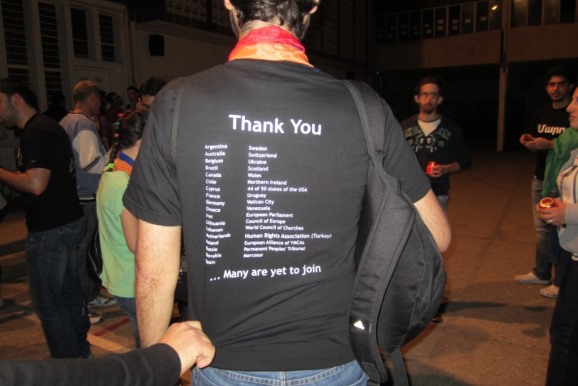

One of the many slogans for recognition

The need to remember

The early migrants from Turkey were mainly focused on survival, and building up a life on the ruins of mass killings and despair. But their children and grandchildren grew up with a nationalist discourse and the corresponding cultural production. The silence that began in Turkey was countered with an immensely active Armenian cultural production abroad, and with the conviction that this history should never be forgotten.

0 Comments

Add a comment