Ethnic identification need not be an expression of Otherness

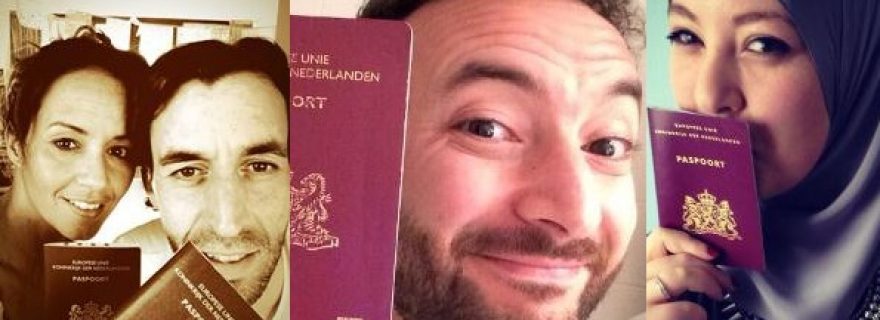

Belonging is a contested issue in the Netherlands. Those who define their identity in ethnic terms are treated with distrust. Why do individuals at times define themselves as ‘Moroccan’ or ‘Turkish’ and does it really make them any less Dutch?

Recently, two Turkish-Dutch parliamentarians were expelled from the Labor party for accusing the Dutch Minister of Integration Lodewijk Asscher of promoting a ‘politics of exclusion’. The minister intends to closely monitor four conservative religious Turkish-Dutch organizations. He argues that these organizations seem ‘too introverted’ and seem to ‘reinforce the Turkish-Islamic identity’, which might lead to a ‘distancing from Dutch customs, norms, and values’. He apparently regards this as inadmissible.

Clearly, being a Dutch citizen, having Dutch citizenship, is by no means a guarantee that you will be accepted as a fully fledged citizen. There is a demand not only to internalize ‘Dutch culture’, but also to define your identity as Dutch, which translates into a demand that you do not define it in ethnic terms.

First of all, in my view, it is important to challenge these rigid ideas about ‘true Dutchness’ and the aspiration for a culturally uniform nation in which all citizens solely identify themselves as Dutch. In addition, society would greatly benefit if more people viewed matters from an anthropological perspective. If ethnic Dutch people, and others, could understand why individuals of Moroccan and Turkish descent refer to themselves as Moroccan or Turkish and understand the relevance of ethnicity for those with an ethnic minority background, this would create a more relaxed attitude towards ethnic identification and ethnic diversity, and a more inclusive atmosphere. As a contribution, I will point out here:

- Ethnic identification does not necessarily threaten people’s ‘Dutchness’, and

- (instead,) ‘Dutchness’ is hampered by the demand to refrain from ethnic identification.

Ethnic and national identification

My study among second-generation Moroccan and Turkish Dutch individuals who have completed higher education examines their ethnic and national identifications. It explores various issues: To what extent do they feel Moroccan, Turkish, or Dutch? When do they present themselves as Moroccan, Turkish, or Dutch? And why do they do so?

Contrary to the current dominant assumption in integration politics that ethnic and national identification are mutually exclusive, my results show that for many (regardless of education level) it is eminently possible to combine identification as Moroccan or Turkish and as Dutch. Such individuals dream in Dutch and speak Turkish with their parents. They value ‘Dutch’ individuality as well as ‘Turkish’ hospitality. They enjoy holidays in Morocco, but could never imagine themselves living there. This idea of dual identification is by no means new (see for example the work of Berry), but does not seem to have filtered through to the dominant Dutch discourses.

The people I interviewed, however, indicated that in order to feel ‘at peace’ with this bicultural identification, they had to detach themselves from the expectations and categorizations of others. They feel pressured by ethnic Dutch and co-ethnics to choose a ‘side’ and to express whether they are Moroccan or Turkish or Dutch. Furthermore, it often happens that they are labeled as Moroccan or Turkish by others (which implies that they are seen as non-Dutch). Such labeling makes it difficult for them to feel and present themselves as Dutch.

The relevance of ethnicity

The common assumption is that ethnic identification is an expression of unbridgeable cultural difference and of unwillingness to be a full Dutch citizen; however this proves to be inaccurate. The study shows not only that ‘feeling Moroccan or Turkish’ does not hamper ‘feeling Dutch’, but also that ethnic identification is promoted by a variety of reasons that enhance the relevance of ethnicity for individuals:

- It can have intrinsic personal relevance. Individuals may enjoy Moroccan food, Turkish music, or familiar religious rituals; these are customs and norms they have grown up with.

- Ethnicity also strengthens connections with people one loves and respects. Certain practices and manners of self-identification help nurture precious social bonds with co-ethnic people, such as parents.

- Ehtnicity can be relevant because one’s ethnic (and migration) background has shaped one’s experiences in particular ways. Growing up in an immigrant family means growing up with particular resources, expectations, and cultural norms and practices.

- Ethnic background also shapes one’s experiences in more discursive ways. The importance that society attaches to ethnicity and ideas about ethnicity influences how one is seen and approached by other people. Certain perspectives can lead to bullying and discrimination and also influence how one perceives oneself. Socially mobile individuals, particularly, feel the responsibility to highlight their ethnic background in order to challenge widespread negative stereotypes.

- Last but not least, ethnicity is often impossible to escape or ignore because of external labeling. When one is labeled as ‘Moroccan’, ‘Turkish’ or ‘Muslim’, this puts ethnicity on the table and forces one to deal with it, in one way or another. Although ethnic labeling is not always intended to be discriminatory, the effect is nevertheless exclusionary because individuals are labeled as ‘the Other’, which denies their sense of belonging as Dutch.

Call for societal awareness

It is important to understand the relevance of ethnicity for individuals with minority backgrounds, and it is crucial to acknowledge that this personal relevance cannot be separated from the relevance attached to ethnicity in society. These insights could make people who belong to the ethnic majority realize that minority individuals are not the incomprehensible, non-Dutch ‘Other’. Nor are self-identifications as ‘Moroccan’ or ‘Turk’ necessarily expressions of segregation and profound cultural difference. Rather, these identifications are ways of dealing with being Dutch and living in Dutch society, with its particular discourses, when one has a Moroccan or Turkish background.

Marieke Slootman will defend her dissertation 'Soulmates. Reinvention of ethnic identification among higher educated second generation Moroccan and Turkish Dutch' on 5 December, 2014 at 14:00 at the University of Amsterdam, Agnietenkapel, Oudezijds Voorburgwal 231, Amsterdam.

This blog is also published on Sociale Vraagstukken (in Dutch).

0 Comments

Add a comment