Women on the Cutting Edge. Logging and Gender in Solomon Islands

Over the past weeks, The Guardian featured a mind-boggling series called Pacific Plunder, which focuses to a large extent on the effects of logging in Solomon Islands. In this blogpost Tessa Minter sheds light on the one story that remains untold: the story of women’s experiences.

Solomon Islands, an archipelago in the Western Pacific of roughly 700,000 people, 75% of whom live in rural areas, has over the past decade become among the world’s biggest exporters of tropical hardwood. The bulk of this so-called ‘South Sea wood’ goes to China, and from there to anywhere, including possibly, the lovely jetty in your town, some invisible yet vital structure in your house, or the comfortable garden chair you sit on.

The facts on poor logging practices presented by The Guardian are infuriating. The images of oil spills, sediment plumes and collapsed hillsides are self-explanatory. The disillusionment of local residents is heartbreaking. And none of it is exaggerated. From the moment that I began my fieldwork in logging concessions in Solomon Islands in 2016, I’ve been witness to the unspeakable environmental and social destruction that the logging industry causes, and the ephemeral nature of the benefits it produces locally – if any at all.

Four decades of foreign-led logging

Since the early 1980s, the Solomon Islands Government’s development narrative has reiterated the indispensable nature of the foreign-led logging industry for the country’s economy. But the systematic undervaluation of logs, as well as both institutionalized and illicit tax evasion, make the logging business far less rewarding for the average Solomon Islander than the narrative suggests.

After four decades of selling out, Solomon Islands’ health care, education and infrastructure are in deplorable shape. The contribution of logging to local employment is disappointing because the sector revolves around round log exports, with relatively little in-country processing. Besides, most skilled labour is hired internationally. Also, it is common knowledge, that the small elite that captures logging royalties, use them for kaikai selen (literally ‘eating money’), which is local parlance for spending money on beer and women.

Meanwhile, largely unregulated logging damages the customary-owned forests and adjacent coastal ecosystems on which Solomon Islanders depend for their sustenance, shelter and cultural identity. Just as worrying, the deep rifts between and within landowning clans over whether or not logging should have happened in the first place, and the sharing and use of royalties, long outlast the actual logging operations themselves. Such tensions easily grow into widespread societal frustration: it is increasingly acknowledged that disgruntlement over the close ties between the logging industry and the political elite is among the root causes of the ‘Tension’, the period of civil conflict that has gripped the country from the late 1990s until early 2000s.

Why women worry about logging

Amidst all the important stories that The Guardian informs the world about, one remains untold. This is the story of women’s experiences in the masculine world of logging. Take for example the women from the island and province of Malaita. Their accounts are part of interviews I conducted with some 200 people (half of whom women) between 2016 and 2019 on how logging operations changed their lives, for better or for worse.

One of these women, who is from East Malaita, told me: 'One thing that I do not like about logging is this. Is it prohibited to let us women be part of the committees or the agreements? Logging comes to everyone, men and women, so why can we not be part of it?'

On the west side of the island, in a neighbouring logging concession, another woman echoed these observations: 'We women don't receive any royalties. The men forget us. We are also not part of any of the [management] committees. [Men] look at us as if we are not big, they look at themselves as big only. [T]hey should also include women in the logging committees […]. Some men are open to it, but they did not put it into action.'

A woman from the same area commented: ‘Fishing inside the bay is a problem now because the mud is covering the corals and some corals die. But the people who like logging, they don’t like to listen to us women. They say they don’t worry about these things. They like logging, they like development. But what kind of development is this when it damages everything?’

‘From happy hour to hungry hour’

These accounts of women’s experiences are the rule rather than the exception. Women had no part in logging negotiations, management or royalty payments in any of the 14 logging concessions that I studied. Their structural exclusion means that their views remain unaccounted for and their problems unaddressed.

This is how it was possible that in April 2017 logging company Mega landed its machines on the southeast coast of Malaita and began cutting down the mangroves adjacent to the village of Mararo in order to construct a log pond, a place for stockpiling logs before they are shipped out.

Mangroves form women’s predominant fishing ground: women and girls of all ages glean the mangrove mud for small fish, shells and crabs on a daily basis. Elsewhere, my colleagues and I have shown how the damage of logging to mangroves and coral reefs leads to a reduction in the consumption of fresh (shell)fish, which forms the primary source of animal protein in Malaitan diets. A school teacher from Mararo explained to me what that means in practice: ‘We used to just collect shells in the mangroves for our late afternoon snacks, but our happy hour became a hungry hour!’

Crucially, this woman refers not only to the importance of the mangroves for sustenance, but for happiness too. The same sentiment is palpable from an elderly woman’s grievances, which she asked me to share with the world, as she was surrounded by most of her eleven children: 'It is a big concern for me that the mangroves are gone because it is the place where I found food. When my children were small, I would go there to find food for all of them: it was close by, so when I heard them cry, I could just go back quickly. [The mangroves] also gave the last food to my husband when he was dying. When he was crying for roropio [mangrove worm], I just went there to collect it for him. It was the last thing he ate before he died. So, when I saw the machines landing, I felt as if I saw my mother dying. I cried. The happiness, the food and the help that the place gave me, are now gone. I want this story to be told, because it makes me cry.'

Hearing women’s voices

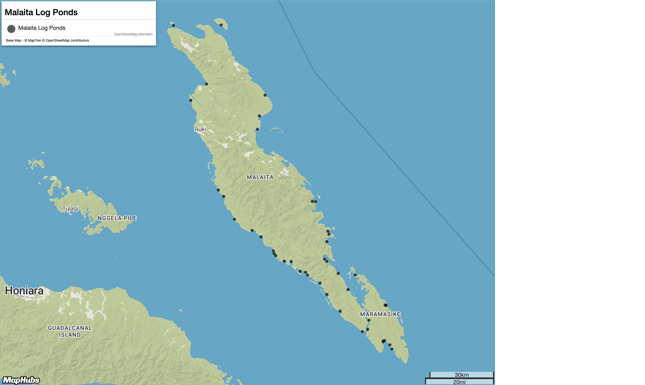

What happened at Mararo is no isolated incident. Log ponds have been created around the Malaitan coast (see map) and many of these were cut from mangrove forests. Had women been involved in the planning and management of logging operations, this might not have happened.

However, women’s marginalized position in logging operations reflects broader gender inequities that mark contemporary Solomon Islands society. The patriarchal nature of land and forest governance and the highly masculinized and monetized character of the logging industry work together to produce a toxic cocktail of exclusion and deprivation for most Solomon Islanders, and for women in particular.

What to do? Clearly, an essential first step is improved implementation of existing national laws and policies related to both logging and women’s rights. But another avenue for change might be found in our own choices as consumers and the pressure we put on our respective governments to take responsibility for the gender implications of the production of wood that enters our markets. For instance, presently only between 25-32% of Europe’s tropical timber imports are sustainably sourced. And even when they are, that does not guarantee that women’s voices were heard in the production process. Yet, even though certification systems may not be perfect, continuously improving them, alongside calling for stricter legislation and enforcement in both producer and consumer countries, is our best bet. Doing nothing is definitely worse.

This Blog was written as part of a study funded through the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 748242.

0 Comments

Add a comment