Spirits up for the tigers: Unsung heroes from a conservation project

Underlying forces at work behind successful wildlife conservation are seldom shared. To show their importance, here are the stories of a politician, a shaman, and a landowner at the Panna Tiger Reserve in India.

Although big names like Jane Goodall or any other hero attract attention for projects, wildlife conservation is always a multi-faceted endeavour involving multiple actors. In 2009, in the Panna district of Madhya Pradesh State, India, the tiger reintroduction program Panna Tiger Reserve (PTR) was initiated with the goal of re-establishing tigers, which had become extinct in the area. Many people from various strata of society, local- regional and national organisations, government bodies and individuals all contributed to the program.

Gate to Panna National Park. Photo Brian Gratwicke.

Through the collective contribution already 25 tigers were born in the reserve to the reintroduced 6 tigers: a great success. The following three individuals have made a significant difference to the Panna tiger reintroduction project. No world wide celebrities, yet of crucial importance in terms of their impact, timing and magnitude, all three of these individuals are heroes of conservation in their own right.

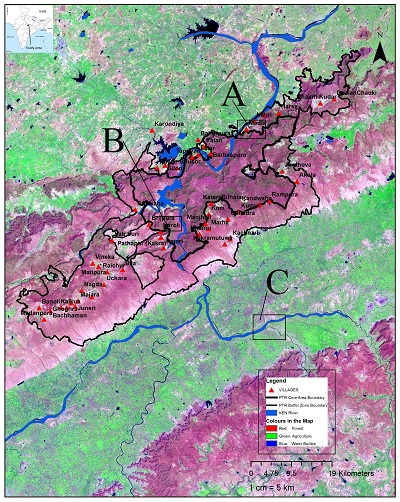

Map: Panna Tiger Reserve and the adjoining forest area A: Case 1 -The Politician; B: Case 2 -The Shaman; C: Case 3 -The Landowners and villagers. © PTR and Shekhar Kolipaka

The Politician

Local politicians play a key role in mobilising or demobilising local community support. After tigers became extinct in the Tiger Reserve, most local politicians took the stance that the Panna Tiger Reserve should be de-notified as a national park and be allowed for commercial exploration of diamonds, sandstone and other minerals for which Panna is famous. They blamed the Panna Tiger Reserve for the economic backwardness of the rural people in the region. In 2010 Chief Minister of Madhya Pradesh to Panna publically voiced this position, saying: “People are more important than tigers…The reintroduction program will stop.”

At that point we despaired for the project. We decided we needed a willing, supporting politician in our core team. Fortunately, Mr. Nagendra Singh, then Minister of roads and an experienced, influential lover of wildlife from the Panna- Nagod- Pahadi area accepted our request and volunteered to help the Panna Tiger Reintroduction Project. With his help, we drew up a strategy to address the local community. Nagendra Singh started to speak to landowners at large meetings, requesting them to support the Panna reintroduction program. Their response was positive, as one member shouted: “The park authorities should have asked us help 10 years ago….We were waiting for someone to ask us help.”

A public meeting in Panna, chaired by Mr. Nagendra Singh. © PTR and Shekhar Kolipaka

By 2014, Mr. Nagendra Singh had chaired over 20 meetings, including meetings with district and state level politicians, bureaucrats, and village level leaders. In this way, he helped the reintroduction program navigate the complex political, administrative and local level barriers. Support for the program increased and land lords on many occasions came forward and helped the project. This experience reemphasises the positive contribution politicians can make to wildlife conservation.

The Gunia (village shaman)

In May of 2014 it was hot, even for Panna, with average temperatures ranging in the high 45 degrees C. During this period Mr. Murthy, field director of PTR, received information about a shy and elusive female tigress that had been sighted by his team (Map, Location B). Female tigresses are important for the success of a recovering population of tigers and Mr. Murthy decided to catch her and attach a radio collar on the tigress to monitor her movements.

A large team of nearly 50 staff started their operations, some of them on elephants, which were used to get the veterinary doctor closer to the tiger. The tigress proved very difficult to corner and after 3 days without success motivation ran low. Some of the staff became sick from the heat exposure, and the elephant mahouts (handlers) became weary and unresponsive. Even the elephants, not used to working in 45 + degree C, started showing signs of defeat.

Then, one team member pointed at a local spiritual site, where villagers of the remote forest of Panna worshipped animistic spirits. They believed that spirits guarded their wellbeing and lived in spirit sites. Most members of the team were locals and believed in spirits and revered tigers as spirits too. Mr. Murthy, who knew about these religious beliefs, asked for the village shaman and commissioned him to organise a spirit calling ceremony.

The spirit site where the ritual spirit calling ceremony was performed. © PTR and Shekhar Kolipaka

The Gunia or the shaman was requested to ask the spirits why the tiger proved so elusive and difficult to catch. In the ritual spirit calling ceremony the possessed Gunias’ body convulsed and danced hysterically as spirits possessed his body. He screamed out loud to the tiger, trying to negotiate a pact for its capture and at the end of the ritual ceremony the Gunia prophesied that the tiger would be caught in 24 hours.

The ritual cheered the staff, who enthusiastically returned to work. Though not exactly within 24 hours, they caught the tiger and all staff praised the spirits. The capture and collaring of the tigress allowed the park management to track the animal’s movements. Within a few months the tigress met a male tiger and they are now together at Panna. The timely contribution of the shaman, motivating the staff, proved to be a very positive step in the Panna tiger reintroduction program. For the villagers the experience was even more powerful. They now know that their spirit tiger can be contacted and that the tiger will guard their forest well.

Landowners and villagers

During a rainy spell in the July-August monsoon months of 2014 a radio collared male tiger of Panna followed the Ken River upstream into a human dominated landscape (seen as a green region in the Map). In two days it reached the area - marked as box C on the map - where it killed a cow and rested during the day in crop fields.

We were not sure how local people would react to this developing situation. We had never faced a situation before of a tiger moving right through human areas and we who knew about its movements were right behind it and amidst people. The worst of thoughts were already setting in, what if the tiger attacks people? What if a panic stricken mob congregated? Should we allow the tiger to retreat naturally or should we just tranquilise it and return it back to Panna?

We had to convey to the people in the villages along the Ken River not to use the river or disturb the tiger. I took a stance that the tiger should be allowed to take its time and decide on the course of its movement. This was an opportunity to learn how a tiger navigates through a human –dominated landscape. However, we did not know how long the tiger intended to stay in the area.

Fortunately, we knew local people sympathetic to the tiger reintroduction program and requested them to help. We had a strategy; involve villagers and let villagers in turn communicate with their own people in their own ways. In a worst case scenario, we could always sedate the tiger and take him back to Panna. Soon a small group of people convened and village heads (Surpanch) chatted about the situation. They, in turn, summoned people from their villages and the snow-ball started rolling.

A traditional announcer was put in place. He travelled through the villages with his drum, shouting out loud about the tiger near the river. By the end of that evening almost all the villages in the vicinity knew about the tiger and neither men nor cattle moved close to the river. There was no panic. The tiger got all the time it needed and after staying in the area for two more days it moved into the hills of Pahadi.

The collared tiger in the left and the male that met it recently on the right. This development is a big step forward to the breeding of tigers in the reintroduction program at Panna. © PTR and Shekhar Kolipaka

Today it resides in Sanjay Tiger Reserve, east of Panna and had also had cubs. The movement of the tiger through human dominated lands and the participation of the locals is a demonstration of local organisation and support of the tiger conservation. These experiences open up new windows of hope to conserve tigers in a large landscape and gives hope and assurance that local communities can and will support conservation.

This blog is written by Shekhar Kolipaka in cooperation with Sreenivasa Murthy (Director Panna Tiger Reserve).

0 Comments

Add a comment